MINNEAPOLIS STAR TRIBUNE

QUIET GUNS PUT WHEEL CHAIR USERS BACK IN THE HUNT.

Dennis Anderson

Published 09/02/2001

Saturday saw the opening of the 2001 September Canada goose hunting season in Minnesota, and north of St. Paul, over a grass field that soon will be filled with houses, the birds were flying.

Below the geese, in tall grass and in portable blinds that resembled rolled hay bales,hunkered an assemblage of people very different from one another, yet very much the same.

One was a tuba player who has performed for kings and presidents, another a sound expert and ballistics buff, another a policeman and another a man who has dedicated himself to waterfowl, particularly ducks, and all things affiliated with them.

In the group as well were three men whose lives are different now than they once were. Injured in accidents -- two by falls, one in a car crash -- the men, hunters each, today moveabout in wheelchairs.

This marriage of disparate lives, experience and expertise was formed Saturday morning ostensibly for the purpose of shooting Canada geese. Much of Minnesota, particularly the Twin Cities, has too many of these fowl, and this early season, expanded in recent years to include most of the state, is meant to thin their ranks.

In that endeavor over the past dozen years or so, no one has been more active, and more generous, than Don (Duckman) Helmeke. It is not too much to say that Helmeke, in spirit at least, is more duck than human.

Helmeke is a passionate hunter. But just as passionately he studies waterfowl and the habitat they need to survive, and he wonders in these troubled times for Minnesota ducks what levers might be pulled that would return to glory the populations of canvasbacks, bluebills and other species.

Helmeke also has been keenly involved for almost 20 years in Capable Partners, a group whose charge is to encourage and help physically challenged men and women enjoy the outdoors, particularly hunting and fishing.

On a different yet parallel sporting track in his life has been Wendell Diller of Oakdale. No less passionate for waterfowl and other game birds than Helmeke, Diller nevertheless has manifested his interests in those subject less on the naturalist's side than the technocrat's.

An inventor, he has developed everything from fleets of motorized duck decoys to shotgun loads that seem to fall only slightly short of automated seekers of feathers and webbed feet.

Given their avocations, it's no surprise that Helmeke and Diller would know one another.

But it wasn't until Saturday morning that they actually needed each other.

A bit of history:

Some years ago, in the late 1980s, the city of Brooklyn Park, like a lot of Twin Cities suburbs, had a goose problem. Too many of these birds were fouling lawns and golf courses.

Yet there was no easily agreed-upon plan for eradication. Houses, even then, seemed to be in nearly as many places as geese. And the Brooklyn Park city council in any case was not particularly enamored of the idea of establishing a hunting season within the community's boundaries.

Yet what to do about the geese?

Enter Helmeke.

"I and other people had been involved with Capable Partners, and we proposed to the city that our group of physically challenged hunters, aided by able-bodied volunteers, be, essentially, the city's goose-control mechanism," Helmeke said. "The council agreed."

So things went for about 13 years in Brooklyn Park. Come September in that city, wheelchair-bound hunters and their helpers would gather in the dark, camouflage their presence and, about sunup, hope to see the distinctive silhouettes of big honkers angling toward their decoys.

"It's been an incredible experience," Helmeke said. "We've had every kind of physically challenged hunter you could think of, from quadriplegics to two men who were blind. Many of our hunts, quite literally, have been the hunts of a lifetime."

Then came last year, when, for the first time, Capable Partners was the subject of a noise complaint in Brooklyn Park. Someone had argued to the city fathers -- and mothers -- that the gunfire was too loud.

Enter now Diller, who in recent years, with the help of friends, including Twin Citians L.P. Brezny (the policeman) and Brian Lungren, has developed a "quiet" shotgun.

Quiet as in puff.

How exactly Diller does this is complex, with patent pending. The short story is this: He affixes barrels up to 7 feet long onto traditional shotguns. Then, utilizing a unique porting system, he dispels gases that accompany shell discharges over a relatively prolonged period of time.

"To buy the additional time, you need additional barrel length," Diller said.

Astute readers might already have concluded that Diller's long guns perhaps could be employed in Twin Cities communities where residents want neither geese nor noise.

Such readers would be correct.

"I have long believed that hunting, particularly for Canada geese but also for deer, will in the future be limited because of the loud sound usually associated with shotgun fire," Diller said. "There are laws against silencers, of course, as there should be. But the long barrels we've developed are legal and, I think, ultimately will be useful in controlling urban geese and even deer."

Diller's initial intent in developing quiet guns didn't concern geese. A crow hunter of what one might call Attila-the-Hun-like intensity, Diller needed a quiet gun to accommodate his forays into rural landscapes that, to his lament and others', are fast filling with pole barns and split levels.

"Many of the roosts that L.P., Brian and I have hunted in rural Iowa, Wisconsin and Minnesota for crows now have houses on or near them," Diller said. "We never hunt closer than is legally allowed. But even at significant distances traditional shotguns make quite a bit of noise.

"So the long gun was at first a way to facilitate our crow hunting. Then, by varying the loads, we made the guns effective for geese and -- when using slugs -- for deer."

Jim Zumbusch, 37, of Maple Lake was in a car accident in 1987, suffered a spinal cord injury and has moved about in a wheelchair ever since.

David Guzzi, 43, of Burnsville fell off a ladder at his home in 1996, dropping 9 feet. He now transports himself in a wheelchair.

Tom Gindorff, 48, of Hugo was working as a roofer 15 years ago when he fell off a ladder from 26 feet. Now he uses a wheelchair to get around.

Dedicated hunters and anglers, the men worried after their accidents that they might never again be able to experience, and enjoy, the outdoors.

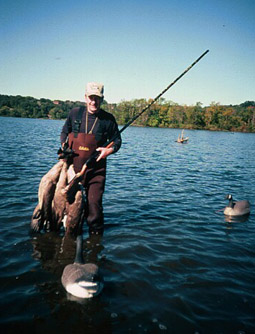

Saturday morning, Zumbusch, Guzzi and Gindorff -- their eyes scanning the skies -- each held one of Diller's long guns in his capable hands.

Nearby, Helmeke, ably aided by Lungren and Brezny, called when geese appeared in the morning blush -- pleading with the birds to cast aside their concerns and descend on the decoys in the near distance

Then there was the tuba player.

Or ex-tuba player.

John Taylor, a freelance writer for American Hunter magazine, published by the National Rifle Association, was for more than 20 years a tuba player with the United States Army Band, retiring in 1991.

A resident of Lorton, Va., Taylor holds a music degree and played with the Buffalo (N.Y.) Philharmonic and the Quebec Symphony, among others, before being recruited by the Army.

More recently he's been a goose guide and, more shamefully still, an outdoor writer, and in the latter role he had come to Minnesota to research a story about these long, quiet guns of Diller's.

No stranger to diaphragm control, Taylor, as one might expect, can toot a goose call well.

So it was that when geese appeared on this first morning of the season, there was a chorus of honks that rang out from the grass, each the product of years of passion and caring for moments just like these.

Not very far away, in homes big and bigger, some people were just rolling out of bed.

Whatever awoke them, a radio maybe, or a phone call, this much is certain:

It wasn't the puff, puff, puff of the long guns so ably employed by Jim Zumbusch, David Guzzi and Tom Gindorff.

Indeed, registering nearly the same number of decibels was the sound of geese falling.

Dennis Anderson is at danderson@startribune.com.

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

ST PAUL PIONEER PRESS

THE NOISE SOLUTION

/ AMAZEMENT OFTEN IS THE REACTION TO AN OAKDALE MAN'S INVENTION, A QUIET GUN THAT IS AS SILENT AS IT IS DEADLY.

Chris Niskanen, Outdoors editor

Published on 09/09/2001

When Sean Coffey's honker call pulled a flock of geese within range, paraplegic Dave Guzzi swung his shotgun with a 7-foot-long barrel and dropped one of the geese dead.

There was a moment of stunned silence -- and not after the goose tumbled out of sky. The morning stillness was barely disturbed when Guzzi pulled the trigger on his extraordinarily long shotgun.

The sharp blast of the 12-gauge was replaced by a muffled fzzzttt. Sitting just four feet away, I was struck by how the shotgun sounded like a loud air rifle. Guzzi, who lives in Burnsville, laid the experimental shotgun between his legs and waited for more geese.

"Pretty amazing, isn't it?'' he said of his gun.

Last Sunday, Guzzi and two other paraplegic hunters with the group Capable Partners were testing a new "Quiet Gun" invented by Wendell Diller of Oakdale, Minn. The site was an alfalfa field in northern Washington County, and the quarry was Canada geese on the second day of Minnesota's early goose season.

Avid hunters Tom Gindorff, 48, of Hugo and Jim Zumbusch, 38, of Maple Lake, also were using Quiet Gun prototypes. Both have spinal cord injuries similar to Guzzi's that make it impossible for them to use their legs. They nevertheless hunt dozens of times a year, for birds and big game, sometimes with the help of volunteers from outdoors-oriented Capable Partners.

By the end of the day, several geese were downed using the Quiet Gun.

For Diller, witnessing the event was akin to Thomas Edison watching a light bulb glow from the workbench. A vision was being realized.

"The Quiet Gun could be the legal solution to shooting and hunting in urban or noise-sensitive areas,'' Diller said.

Though few revolutionary changes in shotgun technology come along each year, Diller is truly breaking new ground with his invention. With the 7-foot barrel, the Quiet Gun bleeds away blast-producing gases through a series of holes, or ports, along the barrel. Diller said the process is similar to letting air out of tire slowly compared to a sudden blow out.

Diller also uses specially loaded shells that propel shot at subsonic, but still deadly, velocity. The extra-long, high-strength aluminum barrel adds just 1.6 pounds to the shotgun.

But there's still the awkwardness of swinging a barrel that is a foot taller than its handlers. The adjustment isn't as difficult as it looks, the inventor said.

It's the most common question I get,'' Diller said. "It takes some practice to learn to swing the barrel, but we took the guys from Capable Partners to the gun range and shot trap and skeet with the guns. I was impressed with how well they did. I often say it requires about 25 percent more lead."

There's certainly a niche for Diller's invention in controlling nuisance urban wildlife, Department of Natural Resources officials say.

"We've been interested in the use of the long, quiet guns in the metro area,'' said Kathy DonCarlos, the DNR's former urban wildlife specialist who, along with her 9-year-old son, has shot Diller's guns at a shooting range.

"We encourage cities and municipalities to use hunters to control wildlife, but noise is one of the things that holds them back,'' DonCarlos said. "We have no formal research study under way, but we think there might be applications for Wendell's quiet guns.''

Diller came up with the idea of the Quiet Gun after years of crow hunting with friend L.P. Brezny in areas increasingly becoming populated. Despite paying careful attention to local ordinances and safety, Diller said he's often uneasy hunting within earshot of homeowners.

"Someone hears a shotgun during crow season, when a lot of other seasons aren't open, and the sheriff comes out, which creates lots of tension, even if you go twice the distance the law requires,'' Diller said. "Birdshot is, of course, not dangerous beyond a certain distance, so often it's the noise problem that generates calls. You can't legally use a silencer, so I got to thinking about sound shock waves and how to release the gases slowly from the barrel.''

An audiophile since he was a teen, Diller is a marketing manager for a company that makes high-fidelity speakers.

"I came at this problem with a technical curiosity,'' he said.

He has spent countless hours experimenting with the barrels and the gas-releasing port system. He's currently mounting the barrels on Browning and Winchester pump shotguns. The system doesn't work on semi-automatic shotguns because there isn't enough barrel pressure to eject the shot shells, he said.

A bit of an iconoclast, Diller travels to hunting spots with his guns in a 1978 electric-blue Plymouth Volare that has 350,000 miles. The super-long guns are carried in special cartons that reach from the front seat to the Volare's rear hatch.

Diller's takes pleasure in demonstrating his gun's applications

Brooklyn Park officials recently made a cornfield off-limits to Capable Partner goose hunters because of noise complaints. Don "Duckman" Helmeke, a volunteer with the group, and Diller went to the field and took measurements of the surrounding noise levels. Cars on a nearby freeway were measured at 64 decibels, while the Quiet Gun measured only 70 decibels. The gun was only slightly louder than the traffic on a Sunday morning.

The Brooklyn Park city administrator was later taken to the field, this time in the afternoon, and Diller fired the shotgun for a demonstration. "The city administrator couldn't hear the shotgun over the traffice noise,'' Diller said.

Helmeke said he's been impressed with the performance of the Quiet Guns."They're not as unwieldy as they look and they're quite lethal,'' he said. "They've proven themselves at 40 yards and beyond.''

Diller is still experimenting with the Quiet Gun and isn't manufacturing them commercially. He doesn't have illusions about getting rich from them, knowing that hunters won't use them unless they absolutely have to.

He's troubled by the way the Twin Cities suburbs are expanding into rural areas and wants government officials to work harder to reduce suburban sprawl. So in an ironic twist, Diller hopes his Quiet Gun doesn't become a necessity for hunters and shooters.

"I hope that the Quiet Gun doesn't become anything more than a specialty product used during situations like the Capable Partner hunts,'' he said.

Chris Niskanen can be reached at cniskanen@pioneerpress.com or (651) 228-5524.